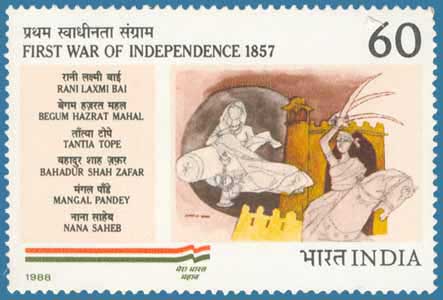

THE RISING of 1857 was an important landmark in the history of India. It marked the beginning of the country's struggle for freedom after a century of uninterrupted foreign domination. The violent outbreak of the Sepoys at Meerut on the evening of 10 May was not a mutiny similar to those which had occurred earlier in the British Indian Army to ventilate certain local grievances of the soldiers. It did not remain an isolated incident. The rebellion soon spread beyond the Bengal Army and assumed the character of a general revolt, which was enthusiastically joined by the civil population of Hindustan. The country witnessed a popular upsurge of deep-seated and widespread bitterness against the alien rulers. The East India Company's Government was swept from large parts of North India and the very foundations of British rule were shaken. It appeared for some time that the Company's Raj had disappeared from the land.

What was the cause of this great convulsion? Some historians attribute it to the 'greased cartridge'. But it is unbelievable that such a vast and popular uprising could have been brought about merely by the new cartridge, howsoever offensive it might have been to the Sepoys. It was the immediate cause, the spark that set ablaze the smouldering fire of discontent. The basic causes of the revolt were complex, embracing all aspects of the impact of alien rule on Indian polity and society.

|

MANGAL PANDE (1831-1857) |

|

|

|

No. 1446 Sepoy Mangal Pande of the 5th Company, 34th Native Infantary fired the bullet that marked the beginning of the great uprising of 1857. The shot fired at Barrackpore resounded all over the country and soon the cavalry corps at Meerut responded adding a new dimension to the revolt. Twenty six year old Mangal Pande was deeply religious and had a good service record. He was disturbed by some happenings like the court-martial of Jamadar Saligram Singh for refusing to use the greased cartridge and the disbanding of the 19th Native Infantry. There was also a general feeling among the sepoys that despite long years of loyal and devoted service to East India Company, the 'native' soldiers were unfairly dealt with and treated with arrogance and their genuine grievances were not redressed. After the impulsive act, Mangal Pande tried but could not shoot himself dead. He was court martialled on 6 April 1857. On 8 April, when he was sent to the gallows he was calm and unruffled as befitted a martyr to a noble cause |

Ever since the battle of Plassey (June 1757) the Company's territorial power had been growing very fast. By 1818, when the last Peshwa was dethroned, practically all the Indian States had either been annexed or had entered into treaty alliances with the Company on humiliating conditions. The British had become the suzerain power and the Indian princes were mere puppets in their hands.

The policy of expansion did not stop there and the few independent principalities on the frontiers were also annexed whenever an opportunity presented itself. In 1843, Sind was attacked and added to the British dominion; it was an act of wanton aggression to cover the terrible disaster which the British armies had suffered in the Afghan war. The revolt of Diwan Mulraj of Multan was used as a pretext for the annexation of the Punjab in 1849. The rights of the minor Maharaja, Dalip Singh, who was under the protection of the British, were set aside. Lord Dalhousie annexed States whenever an occasion arose and often in disregard of solemn engagements. Under his 'Doctrine of Lapse' the princes were denied the long-cherished right of adoption; in this way Dalhousie annexed the Maratha States of Satara, Nagpur and Jhansi and several minor principalities. On the death of the ex-Peshwa, Baji Rao 11, the pension granted to him was abolished and the claims of his adopted son, Nana Dhondu Pant, were disregarded. In 1856, the kingdom of Oudh was annexed. The Nawabs had been the faithful allies of the Company for a long time; but such considerations did not weigh much with Dalhousie, who had a calculated plan to abolish all the Indian States.

The result of his policy was that no Indian prince felt secure, and there was widespread resentment. The annexations also caused discontent among the subjects of the dispossessed princes, as they were bound to them by old ties of tradition. For an Englishman like Dalhousie it was not possible to realize that the people had genuine respect for old dynasties and that they might prefer the old tyranny to the oppression of the new rulers.

The ever widening frontiers of the Company's dominion also resulted in the shutting out of Indians from all avenues of honourable employment. The administrative reforms of Cornwallis, introduced at the close of the 18th century, meant the virtual exclusion of Indians from high posts. The administration assumed an English character. There was perhaps no other case of foreign rule in which the people were "so completely excluded from all share of the government of the country as in British India". To make matters worse, the English administrators gradually became arrogant and there was a wide gulf between them and the people. They could hardly know the feelings of the vast multitude, which providence had placed under their rule.

|

RANI LAXMIBAI (1835-1857) |

|

|

|

Born in a Maharashtrian Brahmin family, 'Manu' was married to Raja Gangadhar Rao of Jhansi and became Laxmibai. The Raja died childless and, despite an assurance given before his death, the company did not permit the adopted child to succeed him and annexed the kingdom. Rani Laxmibai found it hard to bear this humiliation. She stoutly opposed the British expansionist policies with regard to Indian states and was among the principal organisers of the 1857 uprising. In June 1857, she actively led the Jhansi troops against the British army. She demonstrated a rare organising capacity with military leadership, valour and indomitable courage. The Times' correspondent reported on 3 Aug 1858 that "the battle plans were effected mainly under the direction and personal supervision of the Ranee who, clad in military attire ... was constantly in the saddle, ubiquitous and untiring." General Hugh Rose regarded her as "... the woman who was the only man among the rebels". She laid down her life for the freedom of the country on 17 June 1857.

|

This lack of understanding of the feelings of the people is nowhere better illustrated than in the agrarian changes which were introduced in the first half of the 19th century, particularly in the North-Western Province. In the settlement of this province, many landowners were deprived of their lands as they failed to establish their proprietary rights by documentary proof. Investigations were even made into the titles of those who had held estates for many generations before the advent of the Company's rule. At the same time enquiries were held in regard to rent-free tenures. Many failed to satisfy the authorities in regard to the original validity of their titles and their tenures were resumed to augment the Government's revenue. Similarly, in the Bombay Presidency the Inam Commission carried out investigations into a large number of titles to land and many estates were abolished on the failure of the Jagirdars to produce satisfactory documentary evidence in support of their claims.

The landed aristocracy was alienated by these ill-conceived measures. Further bitterness was aroused by the working of the Sale Law and excessive taxation which ruined the landlord and peasant alike. Under the old system land was inalienable, but now it could be sold in default of payment of rent. In the auctions the estates of many land owners were acquired by money-lenders, whose power was growing under the new system but who were total strangers to the rural population. As a result of this 'agrarian revolution' village communities were broken up. The landlords were not merely deprived of their estates but of all hope of honourable .employment. The peasants did not benefit under the new dispensation and were equally aggrieved. Ideas of individual rights and personal freedom did not occur to them and they were opposed to changes in traditional socio-economic relations. The British administrators failed to realize that there was a traditional bond between the talukdars and their retainers arid they all blamed the alien rulers for their impoverishment. When the revolt broke out, the rural population naturally swelled the ranks of the rebels.

Economic distress was also caused in another way by the policies of the Government. The political authority which the Company wielded was employed to serve its commercial interests for many years. Indian handicrafts were ruined as a result of its oppressive policy and the loss of patronage caused by the dissolution of the princely states. The adverse effects of the Industrial Revolution on the Indian economy were also being felt. These factors naturally added to the rising wave of discontent in the country.

The British were different from the Indian people in race, religion, habits, ideas and sentiments. In the 18th century they exhibited a friendly attitude towards Indian society and religions. They had no particular zeal for their own religion and the Company even acted as trustees of some Hindu temples. Missionary activity was discouraged. In the 19th century this attitude underwent a radical change and the British began to interfere with the religious and social usages of the people. Some of the social reforms were indeed introduced with lofty motives, to put an end to evil customs and to ameliorate the condition of the people; but the feelings of those whom the reforms affected were not taken into consideration. The result was that even the abolition of Sati (1829) was not welcomed by the mass of the people. When this evil custom had been banned more than 250 years earlier by Akbar there was no such feeling of resentment on the part of his Hindu subjects. But in the 19th century people looked on the foreign Government with suspicion and they feared that their ancestral faith and caste were in peril. Their fears were undoubtedly based on their own observations.

After 1813 there was a definite increase both in the numbers and proselytising activities of the Christian missionaries, whose avowed object was to convert people to their faith. Missionaries were to be seen everywhere-in bazars, schools, hospitals and even prisons. They ridiculed in public the tenets of Hinduism and Islam. The teaching of the Bible was introduced in some Government schools, and orphans and victims of calamities were often converted to Christianity. The missionaries received support and patronage from highly placed Government officals and the people naturally believed that the Government was in collusion with them to eradicate their caste and convert them to Christianity. The passing of Act XXI of 1850, which enabled converts to inherit ancestral property, confirmed this belief; the new law was naturally interpreted as a concession to Christian converts. Another unpopular act was the one of 1856, permitting Hindu widows to remarry. This was a salutary reform, but according to the sentiments of those days the people apprehended that their religion and society were in imminent danger.

|

KUNWAR SINGH (1777-1858) |

|

|

Kunwar Singh epitomises not only the spirit of liberty but also unparalleled courage and the will to resist injustice at all costs and under any circumstances. He played a major role in the First War of Independence of 1857. Born at Jagadishpur in Shahabad District of Bihar, Babu Kunwar Singh was nearly eighty and in failing health when he was called upon to take up arms. The great warrior that he was, he gave a good fight and harried British forces for nearly an year and remained invincible till the end. While crossing the Ganga on way to his ancestral seat at Jagadishpur, he was wounded in the arm. Undaunted, he severed the injured limb and flung it into the river - as his last offering to Ganga. Soon after, he completely routed the British forces in the battle on 23 April 1858 and passed away the next day. |

The princes lived in an atmosphere of insecurity, the landed aristocracy had been alienated and the mass of the people were disaffected; but their antagonism would not have led to a serious insurrection so long as the Sepoy Army remained loyal. The Sepoys of the Bengal Army were mostly men of high caste from Oudh and the North-Western Province; they shared the general apprehensions regarding the Government's intentions. The Sepoys had won many wars for the Company. They had fought for their masters with unflinching devotion in the most difficult and perilous circumstances. In spite of this, they did not get a fair deal. Their emoluments were very low in comparison with those of the British soldiers and their chances of promotion negligible. They also had grievances regarding the payment of extra cillowances for service in newly conquered territories, like Sind, which were foreign lands to them. The Sepoy's trust in the Government was fast waning. Their bitterness against the foreign masters was intensified by the arrogant attitude of their European officers, and the fellow feeling between Sepoys and officers which had once existed in the Company's Army was a thing of the past. The loyalty of the Sepoys was further undermined by certain military reforms wihch outraged their religious feelings. They had an aversion to overseas service, as travel across the seas meant loss of caste for them: Their feelings had previously been respected in this matter; but in accordance with the new enlistment regulations issued in July 1856 overseas service was made obligatory on all new recruits. The Sepoys construed this as another attack on their caste and religion; their loyalty was severely shaken.

While the country was thus seething with discontent and the Sepoys, too, were agitated, the affair of the greased cartridge came up, One day in January 1857 a rumour went round at Calcutta that the new cartridges to be used in the Enfield Rifle, recently introduced in India, were greased with cow's fat and lard and that this had been done to defile both the Hindu and Mulim Sepoys who would use the cartridges, There was reason to believe that the grease used was of an offensive nature, and the news soon spread to all the military stations. This roused a storm of indignation and kindled the embers of discontent. The introduction of the cartridges hastened the revolt which had long been brewing.

The authorities soon discovered their error and attempted to allay the feelings of the Sepoys, which had been roused by their ill conceived measure. Orders were issued that the new cartridges should not be issued to the Indian regiments and the drill was changed so that the cartridges need not be bitten. But it was too late. Once the suspicions of the Sepoys were aroused it was not possible to soothe them. They were not satisfied even when they were told to grease their cartridges themselves.

The rising wave of discontent manifested itself in several cases of incendiarism at Barrackpur and several other military stations. On 26 February the 19th Native Infantry at Berhampur refused to accept the cartridges given to them. The authorities decided to disband the regiment as a warning to others. Then on 29 March Mangal Pande, a sepoy of the 34th Native Infantry at Barrackpur, attacked the Adjutant of his regiment. His action was a result of the fear in the Sepoy's minds regarding loss of their caste and religion. Mangal Pande was executed after a court-martial; but the trouble which had started could not be stopped by such measures. He was not a felon or a criminal in the eyes of his fellow Sepoys; he was regarded a martyr in the cause of his religion.

|

BAHADUR SHAH 'ZAFAR' (1775 - 1862) |

|

|

|

The last Mughal Emperor, Abdul Muzaffar Muhammad Siraj-ud-din Bahadur Shah, had, for all practical purposes his authority confined to the four walls of the Red Fort - thanks to the machinations of the East India Company. Following the outbreak of revolt in Meerut, troops proclaimed him the Emperor of Hindustan. This resulted in his deposition, imprisonment, trial by military court and exile. A man of aesthetic temperament, Bahadur Shah was a sensitive poet who had adopted "Zafar" as a poetic sobriquet. Before his death in Rangoon, he had lamented the fact that he will not be buried in his homeland |

On 24 April Colonel Smyth of the 3rd Native Cavalry at Meerut called to parade ninety selected sowars of his regiment to demonstrate how they could load their rifles without biting the cartridges. When the cartridges were issued, eighty-five of the sowars refused to accept them. The cartidges were of old pattern, but the Sepoys could not be persuaded to handle even the material which they had used on previous occasions. The offenders were tried by court-martial and sentenced to imprisonment. On 9 May the men were stripped of their uniforms and put in fetters in the presence of the whole brigade and sent to prison. This humiliation drove their Sepoy brethren to frenzy. The following evening, the standard of rebellion was raised. The station was taken by surprise. Led by the sowars of the 3rd Cavalry, the Sepoys broke open the prison and released their comrades, shot many of their British officers and set their bungalows on fire. Chaos followed in the city and there was indiscriminate plunder and killing.

The Sepoys had risen without any plan; but they did not stay very long at Meerut. The majority of them took the road to Delhi forty miles away. Early next morning, after crossing the Jamuna by the bridge of boats, they appeared before the palace of the titular King of Delhi, Abu Zafar Siraj-ud-din Bahadur Shah, a worn-out man of eighty. The King, though shorn of all ruling authority, was still the legal sovereign of Hindustan, and the East India Company held sway over the country on the basis of grants made by his ancestors. There was still a lingering memory of the glorious Mughal Raj, and the last representative of the dynasty was the natural choice of the Sepoys for leadership of the revolt. They urged the old monarch to accept their leadership. He hesitated but finally agreed to their request. This gave legal sanction to the 'mutiny' and the struggle assumed a political colour. Henceforth the Sepoys were fighting in the name of their sovereign.

|

NANA SAHEB (1824 - NR) |

|

|

|

Adopted by Peshwa Baji Rao 11, Nana Dhundhu Pant - Nana Saheb - was the heir presumptive but was denied the title and the pension on the Peshwa's death in 1857. Naturally hostile to the British, he assumed the leadership of the troops at Kanpur and declared war on the Company. Having suffered serious upsets in July 1857, he went to Nepal and was not further heard of. |

The city of Delhi passed into the hands of the 'rebels' in a few hours. The Meerut Sepoys were soon joined by their brethren in the cantonment and the civilian population led by the princes of the royal family. The city was denuded of all Europeans; many were killed and others escaped in disguise when darkness fell at the end of the day. On 12 May the revival of the Mughal Empire was proclaimed with the booming of guns, and the news went round that the English Raj had come to an end. Tidings of the disaster had, however, been flashed to the British authorities in the Punjab before the telegraph office was captured.

The loss of Delhi was a severe blow to the prestige of the Company's Government. There was a comparative respite for a fortnight, however, and the English heaved a sigh of relief. The Punjab, where trouble was expected, remained peaceful. The regiments of Purbiah Sepoys of the Bengal Army posted in different cantonments of the province were disarmed to render them harmless. Those among them who chose to revolt at Ferozepur, Peshawar, Mardan, Sialkot and Lahore, were wiped out. Preparations were set afoot by the Punjab authorities to help in the recovery of the imperial city.

But before the English made an attempt to restore their authority in Delhi rebellions broke out over a wide area covering the North-Western Province, Oudh, Central India and Western Bihar. There were outbreaks of the Sepoys at Nasirabad and Nimach in Central India, and at Jhansi on 5 June. By the second week of June practically the whole of Oudh, was up in arms. The Sepoys had risen at Lucknow on 30 May and the British residence, led by Sir Henry Lawrence, the Chief Commissioner of Oudh, had to take refuge in the Residency. In Rohilkhand, the Sepoys rose at Bareilly on 31 May under the leadership of Subadar Bakht Khan, who later became the Commander-in-Chief of the 'rebel' forces at Delhi. Banaras witnessed a sporadic rising on 4 June and the next day a rising started at Kanpur. Allahabad followed on 6 June.

Apart from Delhi, the main centres of the rebellion were Kanpur, Lucknow and Jhansi. At Kanpur the leadership of the rebels was assumed by Nana Dhondu Pant, popularly called Nana Saheb, the adopted son of the ex-Peshwa, Baji Rao II. He established his government there. He was assisted by his friend and adviser Azimullah Khan, Tatya Tope, Jwala Prasad and Tika Singh. In Oudh, Begam Hazrat Mahal, the wife of the ex-King of Oudh, led the revolt. Her minor son, Birjis Qadr, was proclaimed Wali-i-Oudh. The most outstanding leader of the revolt in Oudh was, however, Ahmad-ullah Shah, the Maulvi of Faizabad. At Bareilly, Khan Bahadur Khan, a descendant of Hafiz Rahmat Khan, proclaimed himself Viceroy on behalf of the Mughal Emperor. In AlIahabad, Maulvi Liakat AIi, a man of humble origin, took over the administration. Rani Lakshmi Bai, the young widow of Raja Gangadhar Rao, began to rule at Jhansi. All these chiefs, however, professed allegiance to the Mughal Emperor who was the symbolic head of the struggle.

The rebellion spread very fast and its suppression proved to be a difficult problem. With the arrival of reinforcements, the task was taken up by the British authorities with determination. Neill was dispatched from Calcutta with a strong force to relieve Kanpur and Lucknow. He arrived at Banaras on 3 June 1857, and after ruthlessly suppressing an outbreak, caused by his own aggressive policy, he left for Allahabad. He reached the latter place on 11 June and within a week the city was secure in the hands of the British force. The Maulvi had to leave the city. In the meantime, General Sir Henry Havelock had been dispatched with fresh reinforcements to restore British authority at Kanpur and Lucknow. He came by rapid marches and encountered Nana's forces at Fatehpur on 12 July. Havelock's advance on Kanpur was fiercely contested by the Indian troops, but superior equipment and better leadership helped him to enter the city on 17 July at the head of a victorious army. Nana Saheb evacuated Bithtir on 18 July and escaped to Oudh. Havelock soon started preparations for the relief of Lucknow, and on 25 July he crossed the Ganga and entered Oudh territory.

|

TATYA TOPE (1814-1859) |

|

|

|

Ramchandra Pandurang Tope was a close friend of Nana Saheb, the Peshwa's adopted son. When Nana was deprived of his father's pension, Tatya Tope also became a sworn enemy of the British. In May 1857 he won over the Indian troops of the Company at Kanpur and commanded the revolutionary forces. After reoccupation of Kanpur by the British troops, Tatya Tope led the revolt in Bundelkhand. Suffering reverses, he reached Gwalior but had to move again. He carried on a guerilla campaign against the British for over an year. Unfortunately, betrayed by a friend, he was captured and executed on 18 April 1859. |

The recovery of Delhi was of supreme importance to the British. On 8 June a combined force from the Punjab and Meerut defeated the rebels at Badli-ki-Serai, near Delhi, and occupied the Ridge the same day. The British force had to wait there for more than three months for reinforcements and heavy artillery to enable them to make a successful assault on the city. During this period they maintained their position on the Ridge with great difficulty in the face of incessant fire from the troops within the city walls and repeated attacks on their positions. More than twenty actions were fought here during June and July.

The British force was strengthened in August with the arrival of John Nicholson. On 3 September the siege-train arrived, and on 14 September the British delivered their assault. The fiercest battle of the campaign was fought on that day and there were heavy casualties on both sides; but by nightfall the British troops had entered the city after blowing up the Kashmir Gate. The fury of battle raged for another six days; the defenders fought courageously but could not prevent the occupation of the city. The palace was taken on 20 September. The following day Bahadur Shah surrendered to Captain Hodson in the shadow of the tomb of his great ancestor, Emperor Humayun. At the same place three of the princes were captured on 22 September and mercilessly shot by Hodson outside Delhi Gate. The city was sacked and thousands of innocent people perished.

|

BEGUM HAZARAT MAHAL (NR - 1879) |

|

|

|

Hazarat Mahal, the Begum of Avadh, was the wife of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Lucknow (who was exiled to Calcutta by the East India Company). She had an inborn genius for organisation'and command. During the 1857 uprising, she seized control of Lucknow with the help of Nana Saheb and other supporters She suffered reverses with fortitude and rejected with contempt, British offers of status and allowances. She sought asylum in Nepal where she died in 1879. |

Meanwhile, Henry Havelock had crossed the Ganga from Kanpur with the object of relieving the besieged troops in the Residency at Lucknow. But his task was a very difficult one. The people of Oudh opposed his advance every inch of the way to Lucknow and twice he had to retreat. It was not till 25 September that he was able to reach the Residency, but he could do no more than add to the garrison. The siege of Lucknow continued, and the rebel forces were augmented by the arrival of numerous retainers of the Oudh talukdars who had joined the struggle.

Meanwhile, Sir Colin Campbell had assumed the office of Commander-in-Chief and with a strong contingent arrived at Kanpur on 3 November. He was joined by the troops from Delhi, and after very hard fighting succeeded in reaching the Lucknow ResIdency on 17 November. He felt, however, that his force was inadequate to hold the city, so he returned to Kanpur with the sick and wounded and the women and children.

On his return to Kanpur on 28 November, Sir Colin found that the town had been occupied by Tatya Tope, who had defeated General Windham on 27 November and obliged him to take shelter in the entrenchment. Tatya had assumed command of the rebel Gwalior contingent at Kalpi (45 miles from Kanpur) and taking advantage of the absence of the British Commander-in-Chief, advanced on Kanpur and joined the troops of Nana Saheb there. Tatya could not hold the city for long; the 'rebel' forces were routed on 6 December. Tatya and many of his troops were, however, able to return to Kalpi.

|

VEER NARAYAN SINGH (1795-1857) |

|

|

|

Narayan Singh Binjhwar, the scion of the Zamindar family of Sonakhan in Chhattisgarh, was born in 1795. During a severe famine, in 1856, he helped the people to save them from starvation. He was falsely implicated and arrested in October, 1856. When the flames of 1857 war reached Chhatisgarh, the masses elected the imprisoned Narayan Singh as their leader and liberated him from the jail. After organising the local people, Narayan Singh had an encounter with the British army near Sonakhan. Moved by the atrocities of the British and the resultant devastation and destruction, Narayan Singh surrendered to the British to protect the lives of his people. His public execution on 10 December 1857 provoked the public and the army contingent at Ranipur, which rose in yet another revolt. Veer Narayan Singh's martyrdom was a memorable event in the history of Chhattisgarh and lent momentum to the freedom struggle. |

In March 1858 Sir Colin returned to Lucknow. The city was regained after three weeks of hard fighting. Begam Hazrat Mahal and other leaders of the revolt were able to make their escape with numerous followers. The fighting in Oudh continued till the end of the year, and many talukdars refused to surrender on the terms offered to them. The rebels were finally driven to the Nepal frontier, to die there in the inhospitable climate or to be captured as prisoners by the Gurkhas who had come to succour the British at a very critical stage of their campaign.

In Rohilkhand, Khan Bahadur Khan's rule came to an end within two months of the capture of Lucknow. Bareilly was occupied by the British force on 5 May. Bahadur Khan escaped, but was later captured on the Nepal frontier, brought to Bareilly, tried and hanged. The Maulvi of Faizabad had entered Rohilkhand after his defeat at Lucknow. He continued to fight undaunted for some time. On 5 June 1858, he attacked Powain and was shot dead by the garrison in the fortress. His head was severed and exposed at the Kotwali of Shahjahanpur, a town which he had attacked a few days earlier. His body was burnt and the ashes thrown into the Ramganga, the worst punishment his enemy could possibly inflict after his death.

In Bihar, the most formidable challenge to British authority came from Babu Kunwar Singh, an old Rajput chieftain of Jagdishpur, in Shahabad district. He assumed command of the Sepoys who had revolted at Danapur on .25 July. Two days later he occupied Arrah, the headquarter of the district. Major Vincent Eyre relieved the town on 3 August, defeated Kunwar Singh's force and destroyed Jqgdishpur. Kunwar Singh left his ancestral village, and after passing through Rewa, Banda, Kalpi and Kanpur, he reached Lucknow in December 1857. In March 1858 he occupied Azamgarh, for which he had been granted a farman by the Wali of Oudh. He had to leave the place soon; pursued by Brigadier Douglas, he hastily retreated towards his home in Bihar. On 23 April Kunwar Singh won a signal victory near Jagdishpur over the force led by Captain Le Grand, but the following day he died in his village.

|

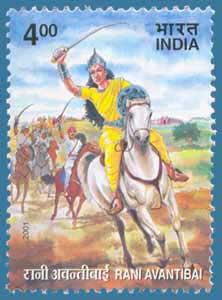

RANI AVANTlBAI (NR - 1858) |

|

|

|

|

Avantibai, the queen of Ramgarh in Mandla District of Madhya Pradesh, was looking after the affairs of the State when the British took over the administration in 1851. She vowed to win back her land, organised the local zamindars and rulers and raised an army of abo,ut four thousand. In 1857, the Rani led her army and in the first encounter with the British defeated Wadington, their commander. However, in subsequent engagements, despite her courage and skill, the Rani could not hold out against the large and well-equipped British army. Faced with the prospect of defeat and surrender, Rani Avantibai chose to sacrifice her life. She joined the ranks of martyrs on 20 March 1858. |

|

The mantle of the old chief now fell on his brother Amar Singh who, in spite of heavy odds, continued the struggle and for a considerable time ran a parallel government in the district of Shahabad. In October 1859 Amar Singh joined the rebel leaders in the Nepal Terai.

After his defeat at Kanpur in December 1857, Tatya Tope carried on a desperate struggle in Central India. Meanwhile Sir Hugh Rose had taken over command of the Central India Field Force. Starting from his base at Mhow. he relieved Sagar in February and on 22 March laid siege to Jhansi, where the indomitable Rani held the reins of government. Tatya Tope came to the assistance of the Rani, but he was defeated in the battle of the Betwa. Jhansi fell on 4 April after a heroic resistance, in which even women and children took part. Lakshmi Bai fled to Kalpi to join Tatya Tope and Rao Saheb. The 'rebels' now suffered a series of defeats and Kalpi was evacuated on 23 May.

Surrounded by British forces on all sides, they were now in sore straits. However, they had courage enough for an act of great daring. Marching to Gwalior, they captured the city and fortress practically without striking a blow on 1 June The Maharaja remained loyal to the British and fled to Agra, but his army joined the rebels, Rao Saheb proclaimed the Peshwa's rule at Gwalior.

Sir Hugh Rose immediately marched to Gwalior and arrived there on 16 June. Three days later the British force occupied the fortress. The Rani of Jhansi fell in a battle on 17 June but Tatya Tope and Rao Saheb were able to escape. Tatya now resorted to guerilla warfare, and baffled the British commanders for many months. He was finally betrayed early in April 1859 by a friend named Man Singh. After a hurried trial, he was hanged at Sipri on 18 April. By that time the revolt had been suppressed.

|

RAJA NAHAR SINGH (NR -1858) |

|

|

|

Ruler of the small state of Ballabhgarh, Nahar Singh was a farsighted person and a votary of Hindu/Muslim unity. He played an important role in the uprising of 1857. Nahar Singh tried to bring together all the neighbouring rulers, especially Begum Samaroo of Gurgaon, Nawabs of Jhajjar, Farrukh Nagar and Rewari. He organised a secret' meeting in the fort of Mukteshwar at the time of Kartik mela which was attended, among others by Tatya Tope. Emperor Bahadur Shah 11 had appointed Raja Nahar Slngh as the Internal Administrator of Delhi. Raja Nahar Singh had tirelessly organised the neighbouring princes and chieftains during the uprising. The British forces had a tough time in controlling the second revolt in the region - Ballabgarh, Gurgaon, Jhajjar and Rewari. He was tried and hanged on 9th Jan 1858. |

The Indian struggle of 1857 was marked by merciless savagery and many innocent men, women and children were slaughtered on both sides. From the beginning, when the British heard of the excesses committed at Meerut and Delhi, they were seized with the desire for vengeance. Wherever the British forces advanced cities were sacked, villages burnt and people slaughtered irrespective of their guilt. Such inhuman behaviour was ascribed to the indignation which the news of the murder of British women and children had aroused. It may, however, be noted that the two massacres-at Kanpur-came after the inhuman acts of Neill at Banaras and Allahabad. The massacres at Sati Chaura Ghat and Bibighar were to a large extent the direct result of the provocation offered by the slaughter of innocent people by Neill. It would be appropriate to quote in this connection the words of Michael Edwardes. He writes: "From the first murder of European civilians at Meerut and Delhi, the English threw aside the mask of civilization and engaged in a war of such ferocity that reasonable parallel can be seen in our own times with the Nazi occupation of Europe and, in the past, with the hell of the Thirty Years' War. No quarter was given to suspected mutineers. Justice became a dirty word, and reason and humanity, feminine frippery."

All Englishmen were not in favour of such cruel treatment of Indians and many raised their voices of protest. Lord Canning, the Govemor-General, genuinely attmpted to put an end to this madness and ordered the proper trial and punishment of those who were suspected of being guilty. For this his countrymen nick-named him in derision, 'Clemency Canning.'

The Revolt had run its course by the middle of 1858, though some fighting continued in the following year. It started as a military rising, but immediately it turned into a war of independence. When the Sepoys placed themselves under the leadership of Bahadur Shah and proclaimed him Emperor of Hindustan, they began to fight for a political cause. Their struggle was then for their king and country. The Sepoys undoubtedly took up arms against their British masters for the defence of their religion, but they were also fighting for political independence as their religion was threatened by the alien government and they wanted to replace it by a political system alien to the soil.

|

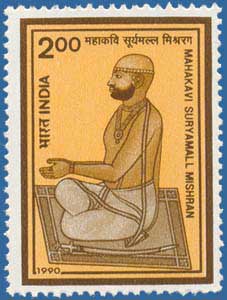

SURYAMALL MISHRAN (NR - 1868) |

|

|

Suryamall had started writing poetry from early childhood. He carried on the tradition of the great bard poets and composed a number of distinguished works, including 'Vansha Bhaskar' - an epic in 10,000 pages. The 1857 war of Independence had a profound effect on Suryamall. He exhorted and inspired the Kings, Princes and Zamindars of Rajasthan to fight and defeat the British. He composed another monumental work, the "Veer Satsai" for this purpose which is noted for its force and vitality, besides patriotism. The failure of the war of independence greatly affected the poet who gave up writing, and devoted his life to the service of his fellow beings. |

The movement spread outside the Army and assumed the shape of a popular struggle against British rule. In many places in the North-Western Province, Oudh and Bihar, the civil population rose independently of the Sepoys. In places where the rising was confined to the Army alone its effects were temporary, but where the civil population joined, the resistance continued for a long time.

In assessing the character of the revolt it would be improper to judge it in the context of the modem concept of nationalism. To assume the existence of such a conception of nationality in 1857 would not be correct, as the country was then passing through a semi-feudal stage. It would also be unfair to judge mid-nineteenth century men by the standards of today. Those who actively joined the revolt had diverse motives, but they were all united in their hatred of the British rule and in their aim to overthrow it. The struggle was as nearly national as it possibly could be under the conditions then prevailing. It was spontaneous and was inspired by a popular impulse to break the shackles of slavery. It brought about the union of different elements and it had wide popular support from almost all classes of society. The struggle created an amazing sense of unity between Hindus and Muslims, and they fought together as brethren. The English attempted to exploit religious differences in order to create dissension in their ranks, particularly in Delhi and Bareilly, but they did not succeed.

The revolt failed in its object. That was perhaps inevitable under the circumstances. But even in its failure the struggle of 1857 forms a significant chapter in the history of India. It was the first large-scale popular uprising against British rule and the first expression of India's urge for freedom. It was undoubtedly the same urge which realised itself ninety years later. The unknown heroes of 1857 did not shed their blood in vain.

(Text sourced from 'Indian Freedom Struggle Through India Postage Stamps' published by the Department of Post, Government of India)