|

|

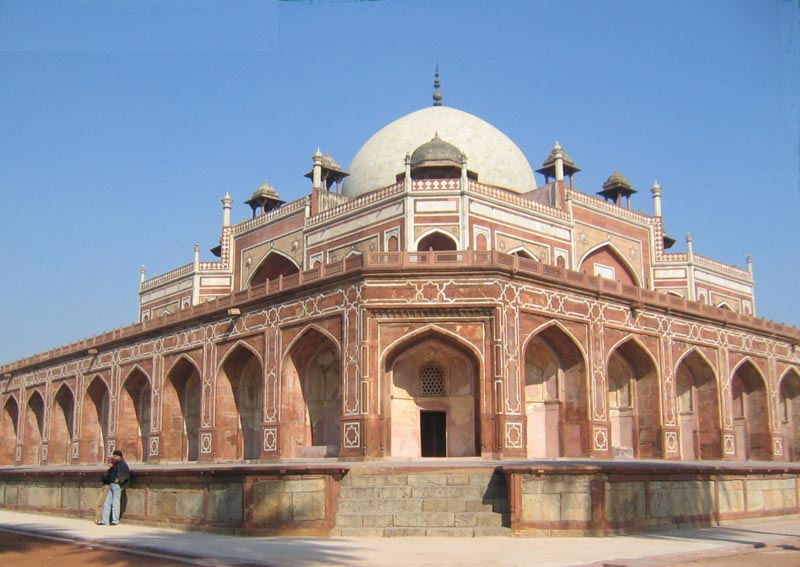

Humayun's Tomb

The life of Humayun, the second Mughal emperor, was marked by struggle and vicissitude. He ascended the throne of Delhi after the death of his father, Babur, in 1530. The Mughal empire was not yet firm on its foundations, and Humayun had to suppress a number of rebellions at the outset of his reign. Early success was followed by prolonged disaster.

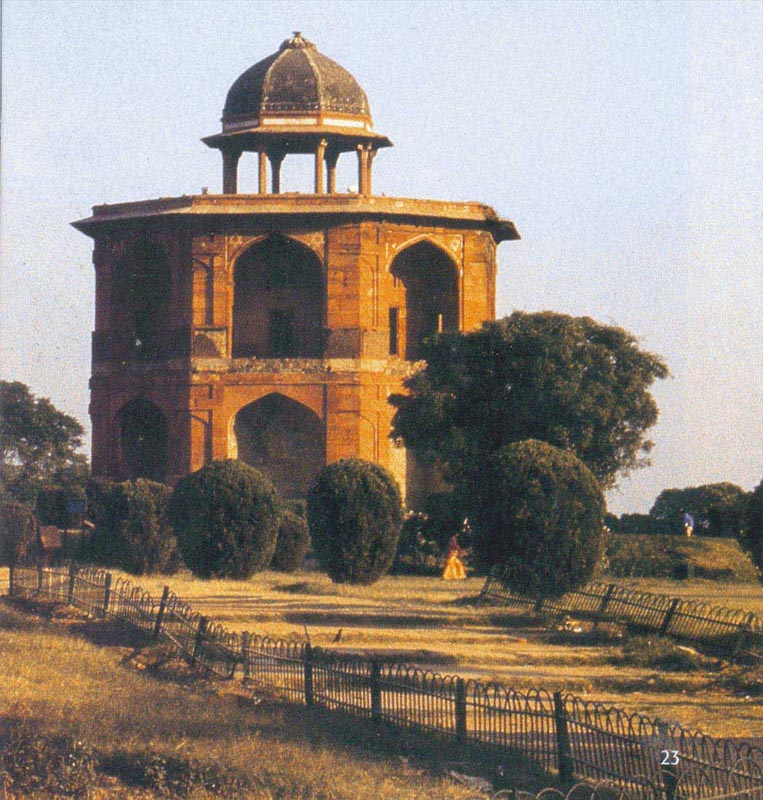

In 1539 Sher Khan, an Afghan nobleman who ruled over tracts of what is now Bihar and Bengal, rose victoriously against him and the vanquished emperor fled the country. He spent 15 years in exile, some of them at the court of Shah Tahmasp of Persia, and in 1555 returned with a borrowed Persian army, recovered his lost dominion and re-established the Mughal Empire. He did not long survive his return and died on January 19, 1556, after a fall on the steps of his library in Sher Mandal, a monument inside what is today called Purana Qila.

|

Humayun in Exile Losing his kingdom at Kannauj in 1540, Humayun fled Agra with his family and treasure. He drifted through Sind and Rajasthan, wandering from fort to fort and kingdom to kingdom in search of refuge and support to take on Sher Shah again. But, neither the King of Sind, nor sundry Rajput rajas offered him concrete help to regain his lost dominions and Humayun decided finally to flee Hindustan. The only bright spot in this meander through desert lands was the fact that on October 15, 1542, Humayun's young bride, Hamida Banu Begum, gave birth to a son in Umarkot. He was named Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar. When he received the happy news, Humayun broke a pod of musk and handed out the fragrant pieces to his men, with a wish that the little boy's ‘fame will, I trust, be one day expanded all over the world, as the perfume of the musk now fills the apartment’. In 1543, accompanied by Hamida and a band of men dwindled to 40, the emperor without a kingdom crossed the Indus and climbed into the mountains of Afghanistan. Repulsed by his half-brother Kamran, the ruler of Kandahar, he decided to cross the mountain passes into the safety of the Persian empire. It was bitterly cold and barren, and the party was ill-equipped for the march. Fortunately they had left the infant Akbar behind in Kandahar in Humayun’s half-brother Askari’s care. Humayun’s efficient general Bairam Khan had been sent on ahead to probe the mind of Shah Tahmasp I and had been assured that his master was welcome in Persia. So, by early 1544 Humayun crossed into Persian territory. Shah Tahmasp’s welcome was more than warm; it was meticulous. His letter to his provincial governor detailing the reception Humayun was to get on Persian soil was 14 pages long. The Shah's firman detailed every facet of the royal reception, from the ‘coloured and smart’ clothes the guard of honour was to wear, down to the specification that the bread to be laid before the hapless Mughal emperor was to be ‘kneaded with milk and butter and seasoned with fennel seeds and poppy seeds’. After his reception at the border, Humayun made his leisurely way to Kazvin, the Persian capital. It was when the two monarchs met here, that Humayun took out a green-flowered purse that he had been carrying in his tunic pocket for three years since he fled Agra. It contained a mother-of-pearl box which he gave to the Shah. Inside, nestled on a bed of precious gems, was a diamond that was to be famous in history as the Koh-i-noor. The Shah entertained Humayun at his court for many months and then, after a lavish feast held in 300 tents to the accompaniment of 12 musical bands, offered him 12,000 horsemen and the wherewithal of war to help regain Hindustan. Humayun set off, but only after he had taken in a trip to the Caspian Sea and another to the wondrous city of Tabriz. It was well into 1545 before he advanced on Kandahar as his first stop to Hindustan. Kandahar could not hold out for long and Humayun rode into the city in September 1545. That, in fact, was the turning point in Humayun's fortunes, for soon after he managed to capture Kabul. For the next seven years Humayun and his brother Kamran fought for ascendancy until Humayun triumphed. Meanwhile in India, the death of Sher Shah's son, Islam Shah, in 1554 had plunged the newly forged Sur empire into anarchy. And Bairam Khan, at the head of the Mughal army, marched right through the Punjab before he was even challenged. Finally, Sikandar Shah, the strongest of the three claimants to the Sur throne, took on the Mughal army at Sirhind in June 1555. Bairam Khan had a smaller army but subtler strategy helped him win India back for Humayun. A month later, Humayun was reinstated on the throne of Hindustan. |

Humayun was buried in Purana Qila, but, according to some scholars, the emperor's remains were removed from there to a supurdgah or temporary tomb in Sirhind when Hemu advanced upon Delhi in 1556 and the Mughals had to vacate the city. He was reburied in the Sher Mandal again when Akbar defeated Hemu, and was moved into the mausoleum erected in 1569 by his widow, Haji Begum, also known as Bega Begum, at an estimated cost of rupees fifteen lakhs.

Scholars have disagreed over the date of construction. Sayyid Ahmad Khan in his book AsarusSanadid (1846 gives the date of its construction as AH 973 (AD 1565) and this date has been followed by all later writers. But an older manuscript of the Siyarul Manazil by Sangin Beg (late 18th century), at present in Delhi's Red Fort Museum, states that the foundation of the tomb was laid in the 14th year of Akbar's reign, that is, 1569.

A radially symmetrical plan, a garden setting and a bulbous double dome on an elongated drum are the main features of Humayun's Tomb. Each of these had strong Timurid associations for the Mughals, who gloried in their dynastic descent from Timur.

Most 15th century Timurid architecture was built to symmetrical plans. These included monuments such as the Ghur-i-Mir (1404) built by Timur for his grandson at Samarkand, and which was his own final resting place as well; Ishrat Khaneh also at Samarkand (c.1460-64); and the shrine of Abu Nasr Parsa in Balkh (c. 1460-64). The Ghur-i-Mir also had a bulbous dome and high drum that was repeated in Humayun's Tomb, the first mausoleum for an emperor of the Mughal dynasty.

|

Timurid Influence on Mughal Architecture High in the snow-sheathed mountains of the Safed Koh is a narrow pass that has seen army after invading army sweep through on its way south into the rich Indo-Gangetic plains. It was through the winding Khyber Pass that Alexander's army marched on its way to conquer the world; it was through here that the Persians, Scythians and Parthians came. And it was through here that a horde of marauding Mongols came sweeping down in 1398, plundering and laying waste all before them. Their warrior chieftain, Timur, was in India for less than six months but in that time plundered so much that, according to one contemporary account, his army was 'so laden with booty that they could scarce march four miles a day'. Among the booty Timur took back to Samarkand were a herd of elephants and a team of stone-masons. These soon became part of a community of artists and artisans in Samarkand which already included painters, calligraphers and architects from Persia and would soon be joined by silk weavers and glass blowers from Damascus and silversmiths from Turkey, as soon as Timur overran those lands. Cultured court life was an integral part of the Timurid ideal. Books and manuscripts were treasures the Timurid princes seldom let out of their sights; and they delighted in landscaping elegant pleasure gardens. Architecture, too, was a passion and the great cities of Samarkand and Herat were studded with magnificent buildings. This intertwining of the aesthete and the warrior in the person of the king was an ideal that all Timur's descendants would aspire to; including those history knows as the Mughals. Historian Ebba Koch sums up the humanistic Timurid legacy of the Mughals, saying that they combined political and military genius with scientific, artistic, even mystical qualifications of the highest order’. She goes on to categorise them as not only founders of cities (Akbar, Jahangir and Shahjahan), architects (Shahjahan), recognised naturalists and horticulturists (Jahangir), polo players (Akbar, Jahangir) and excellent shots (including Jahangir's wife Nur Jahan), but also authors of readable autobiographies (Babur and Jahangir), letters (Aurangzeb) and poems (Babur); they were calligraphers, collectors of art, sponsors of painting and literature, astronomers (Humayun), religious innovators and authors of philosophical treatises and of mystic works (Dara Shikoh and Jahanara)'. Babur, the first of the line in India, was quite close to the Timurid ideal. A born warrior, his attack on north India, which he claimed as part of his Timurid legacy, was masterly. Taking advantage of the internecine squabbles among the Afghan rulers of north India, he swept through the mountain passes and was well into Punjab before his enemy could react. Ibrahim Lodi, the Sultan of Delhi marched out to meet him and the two armies faced each other at Panipat. The Lodi ruler had 100,000 men and a thousand elephants as against Babur's 20,000 soldiers. But Babur had artillery his musketeers under the command of the Turk, Ustad Ali Quli rained chaos into the ranks of the enemy and Babur won Hindustan in April 1526. Babur was a true Timurid, with equal measures of martial and artistic skills. He had an abiding passion for books and gardens, and was an accomplished poet. Few of his gardens in India survive, but the Baburnama does. This memoir spans Babur's transition from a nomad prince to the emperor of Hindustan. His son, Humayun, although not lacking in personal courage, was certainly not as able a commander as his father. Historians contend that he never took time out to consolidate a battle victory and would fritter away months celebrating the triumph in an unending feast of wine, opium and poetry. Humayun was uncommonly superstitious (he never entered a room left foot first) and completely star-struck. According to Abul Fazl, he organised the administration of his kingdom on astrological lines, dividing departments according to the elements - Earth looked after agriculture and architecture; Water looked after irrigation and the royal cellars; Fire was in charge of all matters military; and Air was left with miscellaneous subjects like 'the wardrobe, the kitchens, the stables and the necessary management of the mules and camels'. Each day of the week was reserved for a particular administrative function based on the planet governing the day. So, Tuesday, governed by Mars, was given over to justice, Sunday to affairs of state and Monday to matters of mirth. Humayun, ever-inventive, also had a huge ‘carpet of mirth’ with astrological symbols and planetary positions marked on it. Courtiers and officers were supposed to arrange themselves on it while Humayun, seated on the Sun, cast dice to get them to disport themselves for his amusement. To be fair to him, Humayun set about to develop a new city in keeping with the Timurid traditions of his forefathers. Soon after his accession he laid the foundations of a new city by the Yamuna and grandly called it Dinpanah or Refuge of the Faithful. But, that project never saw fruition for he soon lost his kingdom to Sher Shah Sur. When he managed to regain his patrimony after 15 years in exile, Humayun found that the usurper Sher Shah had completed his city project. He moved into the Sur citadel, today known as Purana Qila, and in fact died there. His temporary tomb or supurdgah was also inside the same fort and it was only much later that his remains were moved into the mausoleum his widow, Haji Begurn, built for him. Humayun's Tomb, the first mausoleum for a Mughal emperor, drew inspiration from 15th century Timurid architecture. Built to a meticulously symmetrical plan, it displayed a range of Timurid characteristics, including the bulbous double dome on a high drum; a high portal in the front elevation; coloured tilework arranged geometrically; and arch-netting in the vaults. Here it combines with decidedly pre-Mughal elements like the combined use of red sandstone and white marble inlay; lotus bud-fringed arches, perforated stone jali screens, wide chhajja eaves and corbelled ornamental brackets. So, in a sense, the monument of the Humayun's Tomb became an architectural metaphor for the Indianisation of the Mughals. |

As one of the first important buildings the Mughals erected in India, Humayun's Tomb introduced purely Persian features to the subcontinent, but it also drew several elements from the land it was built in. The red sandstone and white marble, for instance, was a common feature of 14th century architecture of the Delhi Sultanate.

The mausoleum of Humayun and the enclosure-walls are built of three kinds of stone. The walls and the two gateways are of local quartzite with red sandstone dressing and marble inlay. The red sandstone for the main building came from Tantpur near Agra and was used with white marble from Makrana in Rajasthan.

|

West Gate |

In the centre of the garden, the mausoleum itself rises from a wide and lofty platform about 6.5 metres high, which in turn stands upon podium just over a metre high. The latter is the only feature of the mausoleum built of quartzite, the remainder being entirely of red or yellowish sandstone with marble panels or outlines and a marble covered dome. Each side of the high terrace is pierced by 17 arches, while the corners of the structure are chamfered, giving the monument a pleasing depth. At each corner, an oblique arch cuts the angle.

The central arch on each side opens on to an ascending staircase. To the east of the southern stair a horizontal passage leads to the actual tomb below the monument. The remaining arches open into cells, most of which contain subsequent and subsidiary tombs. The floor of the terrace is paved with red sandstone and contains a number of un identified graves.

|

Mirak Mirza Ghiyas Humayun’s tomb is said to have been built under the supervision of Mirak Mirza Ghiyas, an architect of Persian descent. It is said that Haji Begum was greatly taken with the Persian style of building and commissioned Ghiyas precisely because of his familiarity with the architecture of that region. And the Persian builder, who had worked extensively in Herat and Bukhara, gave India its first dome in the Persian tradition. |

Inside, the octagonal tomb chamber rises through two storeys and is surrounded by smaller octagonal chambers at the diagonal points. These chambers also house a number of other tombstones, making Humayun's mausoleum almost a family one. The central hall containing the cenotaph (vertically above the actual tomb in the basement) is roofed by a double dome carried on squinches, with plastered interlace in the spandrels, It is in three stages, of which the central is a gallery and the uppermost a clerestory. Most of the openings are filled with sandstone grilles.

Between each of the octagonal wings on the diagonal sides of the central tomb lie the great arched lobbies that dominate the exterior elevation. Although varied in terms of their numerous panels and recesses, these conform essentially to the three-fold scheme characteristic of Persian architecture, the great central arches being flanked by a smaller but emphatic arch in each wing.

| Garden in Humayun's Tomb with West Gate in the distance |

Humayun's Tomb was among the first structures in India to use a double dome. This device, a favourite of Persian builders, gave a building an imposing exterior height but kept the ceiling of the central hall in proportion with the interior heights. The dome is also remarkable in that it is the first major full dome to be seen in India. Earlier domes were not full in the sense that their shape never traced a full semi-circle.

The outer dome of Humayun's Tomb is covered with marble and is bulbous in shape. It is supported by pavilions or chhattris above the wings and portals. These, historians believe, served as a madrasa or college in the days when the tomb was a living monument. The chhattris serve the added purpose of masking the drum from view. These pavilions, augmented by carefully graded pinnacles at all angles of the building, unite the soaring outline of the dome with the horizontal lines of the main structure and give strength and coherence to the design.

|

Domes Indian indigenous architecture was unacquainted with the dome until the advent of the Muslims. The roofs of Hindu temples were either flat-topped or modeled on mountain sikharas to meet in a peak above the sanctum sanctorum. Muslim builders, on the other hand, had long been accustomed to arcuate construction and used squinches to raise domes above their buildings. When the Islamic forces overran north India in the 13th century, the Muslim rulers were keen to replicate their domed buildings here. But, the local workmen were unfamiliar with the technique of raising domes and the earliest domes constructed by them, like the one that covered Iltutmish's Tomb (1235) in the Qutb Complex, were amateur efforts and soon caved in. When the local builders finally mastered the art of constructing domes, they built them as half domes, that is domes that did not sketch a complete semi-circle. In fact, most Indo-Islamic monuments until the 15th century had half domes raised above them and it is only with the buildings of the Lodi dynasty (1451-1526) that the domes began to curve a full semi-circle. The rounded shape of the early Indo-Islamic dome differed greatly from Persian domes, which were bulbous semi-circles rising from a high drum. The first time this Persian style dome appeared on the Indian skyline was in Humayun's Tomb. The dome of Humayun's mausoleum is significant on another count - it is the first major double dome to be constructed in India. A double dome is one composed of two shells, with a gap between the two layers. The outer shell provides the elevated dome imposing height while the considerably lower inner shell provides the central chamber a roof proportionate to its dimensions. This style of raising a dome had been prevalent in West Asia for a while before Mirak Mirza Ghiyas brought it to India. |

The walled enclosure of the tomb is entered through two gates. The main gate to the south, which is now closed, and a less imposing west gate. The south gate is a towering 15.5 metres high. It stands on a podium approached by a flight of five steps. The ground floor comprises a central hall, octagonal and domed, with rectangular wings. There are square and oblong rooms on the first floor of the gateway. The outer angles are adorned with octagonal pinnacles topped with a lotus design. The gate is flanked externally by screen walls with arched recesses.

Adjoining the south gate is a compound on the west, 146 metres by 32 metres, built against the exterior face of the main enclosure-wall. It contains a low-roofed verandah, with 25 arched entrances and was possibly meant to accommodate the many attendants of the royal tomb. Its main exit is towards the south, but it is also connected with the tomb by a small doorway. There is another dilapidated building flanking the eastern side of the gate externally. Both this building and the verandah are later additions.

|

|

|

Emperor's Cenotaph |

The west gate, by which visitors now enter the tomb-enclosure, also stands on a podium with five steps and is two storeys high. It consists of a 7 metre square central hall, with square side-rooms on the ground floor, and oblong rooms on the first. It is approached from the front and back through portals 10.7 metres high. The gate is flanked externally with arched recesses and measures 15 metres from the floor-level to the parapet. It is surmounted at the outer angles by small chhattri pavilions, 1.5 metres square.

The northern, southern and western walls of the enclosure are of plastered rubble and are 5.8 metres high. The interior face contains recessed arches with pointed heads and the outer face is crowned with merlons in relief.

|

Red Sandstone and White Marble Indo-Islamic builders have favoured this architectural scheme ever since it made its first appearance in the Alai Darwaza added to the Quwwatul-Islam Mosque by Alauddin Khalji in 1311. It remained prominent through the Delhi Sultanate until Ghiyasuddin Tughluq's Tomb was built around 1325. The medium is then eclipsed for the better part of the 15th century and is seen again only in the Lodi period Moth ki Masjid (c.1488-1517). Under the highly aesthetic MughaIs, the combination again becomes the standard means of finishing a building. The mosque of Jamali-Kamali (c.1528-29), the Qala-i-Kuhna Masjid (c. 1534), and the tomb of Ataga Khan (c.1566-67) are early Mughal monuments in Delhi that use the scheme |

On the east or the river side, the enclosure-wall is just about 1.5 metres in height, except for some 64 metres towards the south end, where it is again 5.8 metres high. Only this portion of the eastern wall is plastered, and it contains recessed arches on both faces. The lower wall was doubtless meant to afford an open view of the river Yamuna from the tomb and the garden. The enclosure-walls were built in several stages, as is indicated by breaks in the bond.

Towards the centre of the inner face of the north wall stands an arcaded pavilion on a platform 2.1 metres high. It contains an octagonal tank, about one metre across, and the room appears to have been a hammam or bath. It is plastered but undecorated. Behind this pavilion, on the north side of the enclosure-wall is a rubble-built circular well, which supplied water both to the bath and the channels of the charbagh.

|

|

South-West Face |

The centre of the eastern wall has a more decorative pavilion, with a verandah along its east front, which faces the river. The details of the sandstone columns and elaborately cusped arches indicate that this pavilion is a later addition, probably of the 17th century.

|

The Gardens of the Mughals The concept of paradise as a garden is one of mankind's oldest ideals. The image of a place of perfect eternal peace and plenty can probably help make a difficult temporal existence meaningful and its transitory nature acceptable. The paradise promised in the Quran consists of several terraces of gardens, each more splendid than the last. The ancestor of the Mughals, Timur, took great pride in the gardens he built. Timur's gardens, within which were rich encampments decorated with plunder from captive nations and his throne over the water courses representing the four rivers of life, became famous world-wide. Babur, the first Mughal emperor, built many innovative gardens, always with water. A layout for gardens, as described in his memoirs, set the design for all future Mughal gardens, known as the charbagh or ‘four-folded garden’. The introduction of new materials might have changed appearances, but the basic design of Mughal gardens remained the same. On his death, Babur was first buried at a garden in Agra and later, in accordance with his expressed wish, was interred in a garden in Kabul with a simple marble cenotaph covering his body. Babur introduced into India the TimuridPersian scheme of a walled-in garden, subdivided into four quarters by raised walkways and canals. Art historian Ebba Koch writes that such a garden became the foundation stone for the development of Mughal Agra as a riverbank city with a succession of walled gardens on both sides of the Yamuna. Of Babur's gardens in India the rock-cut Bagh-i-Nilufar (Lotus garden) at Dholpur (1526-29) is preserved to some extent. Its modest structures are far less than what one would expect from the emperor's descriptions in his memoirs, Baburnama. Of his charbagh or Bagh-i-Hasht-Bihisht (Garden of the Eight Paradises) in Agra nothing much remains. According to a recently discovered 18th century plan of Agra at the Jaipur Palace Museum, the garden was situated on the other side of Yamuna adjoining the Mahtab Bagh and almost opposite the later Taj Mahal. However, it is the later imperial tomb gardens, of which Humayun's Tomb is the first, that are considered the greatest innovation of the Mughals in garden architecture. In all the great tomb gardens – Humayun’s in Delhi, Akbar's in Sikandra, Jahangir's in Lahore, the Taj Mahal, the tomb of Itmad-ud-Daulah in Agra and the Bibi ka Maqbara in Aurangabad - the design of the tomb and garden were treated in unison. Each was meant to enhance the beauty of the other. Symbolically, these were the perfect embodiment of the Islamic ideal, the ultimate paradise garden, with the emperor forever in paradise. The large square enclosure, divided with geometric precision, was the ordered universe. In the centre, the tomb itself rose like the cosmic mountain above four rivers represented by the water-channels. Eternal flowers, herbs, fruit, water, birds such as those of paradise added further character h) the tomb garden. Humayun's Tomb is the first preserved Mughal garden on a classical charbagh pattern. The paved walkways (khiyabans) that divide the garden into four parts terminate in gatehouses and subsidiary structures. With the tomb as its centrepiece, the garden enclosure occupies 30 acres. Enclosed within a 6-metre high arcaded wall on three sides, it is divided into quarters by causeways 14-metres wide. The causeways are provided with stone edging, with a narrow water channel flowing along the centre. Each of the quadrants is further divided into eight plots with minor causeways. The intersections of these causeways are marked by rectangular or octagonal pools, that are occasionally foliated. Water entered the garden from the north pavilion, and also from the western side. Terracotta pipes fed the fountains and drained away excess water. The tomb of Akbar in Sikandra (1613) outside Agra stands in the centre of a classical charbagh whose main walkways terminate in one real and three blind gates. |

Humayun's Tomb marked the end of the sombre style of early Indo-Islamic architecture and laid the foundation of the ornate style that characterised the mature Indo- Islamic architecture and culminated in the Taj. The rigid main lines of the building are diversified by chhattris or pavilions essentially Hindu in origin and, without impairing the strength of the design, give it a coherence foreign to its Persian prototypes.

|

|

Sher Mandal - Purana Qila |

|

|